Why we are trapped in the era of circular-ish — and how to break free

While brands tout their circular innovations, most deliver only ‘circular-ish’ solutions — small tweaks that fall short of true transformation. This article explores the state of circular-ish solutions and how companies might finally escape this trap.

In early September, Crocs, the American footwear company, announced that it had reached 25% bio-circular content in its proprietary Croslite material, which is used to make Crocs shoes. Crocs explains that it uses “plant-based byproducts that would have otherwise ended up as waste, like cooking oil from the food industry, to make its Croslite material.”

Crocs wasn’t the only company sharing updates on its circular efforts. Over the last couple of weeks, several interesting announcements on circular innovations have been made. Lego shared that “it is on track to replace the fossil fuels used in making its signature bricks with more expensive renewable and recycled plastic.” The company aims to produce all its products from renewable and recycled materials by 2032. Pandora, the world’s largest jewelry brand, updated that it “is now crafting all jewellery with 100% recycled silver and gold.” Diageo announced a new trial for a paper-based 70cl Johnnie Walker Black Label bottle. And the list goes on.

But, are these truly circular innovations? Yes, they do offer a transition from using one material to another that is deemed to be more sustainable. However, do these changes really reflect the essence of circular economy as a “a system where materials never become waste and nature is regenerated”? Do they embody the three principles the circular economy is based on, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Eliminating waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems?

I doubt it. If anything, the examples I shared represent a circular-ish economy, not a circular one.

What is circular-ish?

It’s a term coined by Joe Iles, Design Lead at EMF in 2022. Iles suggested that it reflects a state of work in progress on the circular economy, where “we translate the circular economy from premise to pragmatism.” Building on Iles’ characterization of circular-ish, I’d like to offer a somewhat more nuanced definition: Circular-ish is an innovation with circularity aspirations that nevertheless fails to entail most, if not all, of the three circularity principles: waste elimination, material and product circulation, and regeneration. It focuses mostly on changes at the materials level or offers incremental business model modifications that do not challenge the core ways in which companies creates and deliver value. In all, it does not reflect a system transformation, but rather a system tweak.

Both Iles and I recognize the importance of design in developing a circular economy and the critical need to redesign the unsustainable linear economy we currently live in. However, a key difference between Iles’ view and mine on circular-ish is that he sees it as a temporary phase in the circularity journey, which is to be expected given the immense scope of shifting from linear to circular systems and the challenges of finding the right paths forward. I, on the other hand, believe this phase is not a stepping stone toward systemic transformation but rather a muddy swamp that traps us — and will likely continue to do so — because of the mental model that underpins our economy.

Before diving into the circular-ish swamp, I want to be clear that I do believe in the value and potential of circularity. I see circularity not only as a sustainability strategy, but also as potentially “the super league of sustainability,” as Viviane Gut, the former Head of Sustainability at On Shoes described it. After all, as I point out in my book Rethinking Corporate Sustainability in the Era of Climate Crisis — A Strategic Design Approach, circularity offers a clear vision of transforming critical environmental challenges into business opportunities through innovation, new business models, and disruptive technologies. I remain convinced that this vision holds immense potential to make a meaningful difference.

Therefore, my critique of the current state of circularity is not a reflection of disbelief in what circularity could achieve, but rather an acknowledgement of the powerful forces that have shaped the circular economy into what it is today — circular-ish. In that sense, circular-ish is not an organic evolutionary state, but a mirror of an economic system where bottom-line considerations take precedence over sustainability, dictating how companies operate. In other words, circular-ish is another form of sustainability-as-usual, where companies aim to create some positive environmental impact — but in ways and at a pace that do not threaten their core business and the market’s performance expectations.

As a number of scholars point out, the “circular economy does not amount to a sufficiently radical transformation since it does not address issues such as hyper-consumption, techno-optimism, and economic growth.” In my view, this offers a useful lens for understanding the current state of a circular-ish economy, which focuses primarily on efficiencies, waste reduction and a shift toward recycled materials, rather than challenging the fundamentals of a growth and consumption-based economy. As such, the circular-ish economy has fostered an innovative space that remains inherently limited in its ability to generate substantial value propositions aligned with planetary boundaries and interspecies justice.

Even with its limited focus, the circular-ish economy fails to move the needle as demonstrated in the circularity gap report. Published annually since 2018 by the Circle Economy Foundation, the report measures and monitors what percentage of global economic activity is circular, or the share of secondary (recycled) materials consumed by the global economy. According to the authors of this year’s report, “the share of secondary materials declining steadily since the Circularity Gap Report began measuring it: from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% just five years later in 2023.” The reason for this is simple — although the use of secondary materials is growing, the total volume of materials consumed is increasing even faster due to rising consumption and economic activity.

A good example of the circular-ish economy is Apple, which may even be considered its poster child. The company claims that it aims “to make products using only recycled or renewable materials — so we prioritize, responsibly source, and recover materials.” This approach is indeed reflected in every new product launch, from new iPhones with increased renewable content, such as 100% recycled rare earth elements, to the new Apple Watch, which contains 100% recycled cobalt in the battery. However, as Gary Cook, who directs global climate campaigns at Stand.earth, told Bloomberg, “recycling is actually a distraction. When it comes to lessening climate impacts, “repair is much more important.”

As the Bloomberg article points out, Apple prioritizes investment in recycled materials over extending the lifespan of its products through optimization for durability and repair, simply because the company’s business model is based on selling as many iPhones, Apple Watches, and other products as possible. Apple’s belated shift on the right to repair is one example — the company only revised its position after significant legislative pressure, but even now it appears to make repair only marginally easier. It certainly doesn’t seem likely that Apple will abandon its planned obsolescence-driven strategy, as it continues to present new products annually, encouraging customers to purchase them instead of holding on to “old” ones.

Can circular-ish be a stepping stone to system change, which according to Kania, Kramer, and Senge, is “about shifting the conditions that are holding a problem in place”? As things stand, the answer is probably no — and it’s not due to lack of potential. After all, circular-ish is the floor for circularity, not the ceiling. The problem is that circular-ish can’t evolve as long as the fundamental structures remain unchanged. As long as sustainability-as-usual dominates business practices and circular efforts are constrained by a shareholder capitalism mindset, we remain trapped in circular-ish. Any improvements we see are likely to be incremental — small tweaks in a system that remains inherently unsustainable.

However, this doesn’t mean there aren’t design hacks to help companies break free from the constraints of circular-ish innovation. Below, I outline three strategies they can implement to achieve this. For those who might wonder if regulation should be the ultimate focus — yes, regulation is certainly key. But in a climate where there is diminishing appetite for robust sustainability and climate legislation, it’s vital to explore other avenues in the meantime. Moreover, these strategies can also help pave the way for future regulation by activating companies as policy first movers. By embracing one or more of these strategies, businesses can help normalize key policies and create a more favorable environment for policymakers working to push this agenda forward on a national level.

Here are the 3 suggested strategies for companies:

1. Creating an immune system

The current economic system resists change, as systems tend to do. Different actors who benefit from the status quo or fear changes that challenge their assumptions about how the world works will actively oppose companies attempting to move away from the circular-ish sandbox. Overcoming these pressures requires companies to develop an immune system that shields their efforts to adopt circularity in a meaningful way, or put differently, embracing circular innovations that shift the conditions holding their unsustainable practices in place.

One way for companies to do it is to operate as private entities. For public companies, it is far more difficult withstand market pressure to generate solid growth and short-term returns. These pressures suggest that even when a company takes sustainability more seriously under the leadership of a courageous CEO, it can quickly revert back to business-as-usual territory once a new CEO — less willing to push back against investors — takes over, as seen in the case of Unilever.

It also seems clear that one of the key reasons a company like IKEA — one of the few whose efforts aim to move beyond circular-ish with its goal to become fully circular by 2030 — takes circularity more seriously than others is because it is privately-held. It is likely easier for private companies to develop strong sustainability culture and DNA that can translate into genuine efforts to decouple economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.

But, what about public companies? What can they do, assuming they’re not going to become private, to develop an immune system?

For these companies, the answer lies collaborative efforts to develop ecosystems of circular innovation that can withstand market pressures. One example is the reusable cups pilot that Starbucks, Dunkin’, KFC, Burger King and others are running together in Petaluma, California. Collaboration is essential not only because of the complexity of these challenges but also because adopting a circular practice, such as the use of reusable cups, is likely to result in higher costs as long as externalities remain unaccounted for in the economic system. For any company acting alone, justifying increased costs to the markets would be difficult. However, when multiple key competitors take the same step together, it creates a permission structure that enables companies to resist market pressures and invest in circularity efforts — even if those efforts carry a potential short-term negative impact on the bottom line.

2. Creating a virtuous feedback loop with 1.5C lifestyles

One key feature of circular-ish innovations is that they usually do not challenge consumption patterns at all — or if they do, it is only in superficial or marginal ways. Moving away from circular-ish requires addressing consumption patterns more seriously, but to do so companies need the buy-in of customers. In other words, companies that want to move away from circular-ish innovations must cultivate customer interest and engagement in these efforts.

Companies cannot significantly redesign their business models around circularity unless enough people find these changes attractive. This applies to shifts toward refillable packaging, making repair the norm, buying second-hand, or offering access-based solutions instead of ownership-based ones. In all of these cases, such efforts are unlikely to succeed if people don’t embrace them. And if customers resist these changes, companies will have far less incentive to transition from the less-impactful but also less-risky circular-ish state they currently operate within.

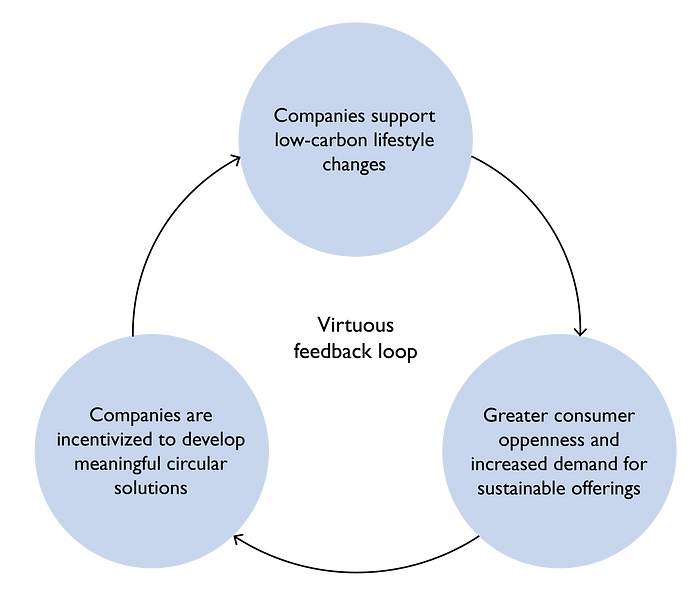

To achieve this, companies must embrace a systematic approach that drives a shift toward 1.5°C lifestyles and initiates a virtuous feedback loop, which will create stronger demand for robust circular solutions. This feedback loop takes shape when a company’s efforts to promote low-carbon lifestyle changes — such as supporting 1.5°C-compatible social norms and using storytelling capabilities to shift public perception and attitudes — generate greater consumer openness and amplify demand for sustainability offerings. In return, these shifts further incentivize companies to develop genuinely circular innovations, allowing them to move beyond circular-ish solutions.

This is a delicate dance, but companies must participate in it if they are interested in fostering a transition from circular-ish to genuine circular innovations. Over decades, businesses have intentionally cultivated an (over)consumption culture that overlooks sustainability impacts. To move forward with circular solutions, companies need to redesign the systems and incentives that influence consumer behavior, creating an environment where bold circular innovations can thrive. In a forthcoming study, I identify three key opportunity domains where businesses can make impactful interventions to support a shift toward 1.5°C lifestyles, reinforcing their sustainability efforts. Leveraging these domains effectively could enable companies to break free from circular-ish practices and make progress toward meaningful circularity.

Selfridges exemplifies this approach by focusing not only on transforming its business model but also on shifting customer mindsets. One of the core pillars of its agenda is “changing the mindsets of teams, communities, and customers to create a truly inclusive retail culture in which people and planet come first in every decision.” This strategy aligns with the company’s sustainability goals while engaging customers in reimagining the future of retail, fostering awareness, and building openness toward new, sustainable ways of meeting their needs.

3. Fostering a circular culture within the organization

While the first two strategies focus outward — on creating ecosystems of circular innovation and supporting customers’ shift toward 1.5°C lifestyles — this third strategy turns inward. It seeks to build internal counterforces that enable companies to develop a stronger and more resilient organizational DNA, one capable of resisting short-term market pressures or leadership decisions that may cave to such pressures. The cornerstone of this approach is fostering an organizational culture that is both deeply aligned with, and actively advancing, circular principles and strong sustainability goals.

Transforming from circular-ish to full circularity requires more than isolated initiatives — it demands systemic change in how companies operate, think, and behave. As highlighted by Bertassini et al., organizational culture is a key enabler of circular transformation, ensuring sustainability is not just a superficial add-on but embedded into the organization. The researchers emphasize that values, beliefs, and mindsets play a crucial role in fostering a circular economy. They explain that “organizational changes towards CE require values modification and alignment with CE principles and strategies.” Moreover, they highlight that a “CE-oriented mindset’ consists of beliefs or attitudes aligned with these principles, which shape how an organization interprets and responds to situations.”

To assess what the organizational culture should look like in order to give adequate support to adopting impactful circular measures, we can use Bertels et al.’s extensive research on how to build a sustainable culture. This involves creating a culture where members of the organization hold shared assumptions and beliefs about the need to adopt and advance meaningful circular initiatives. Transitioning the culture requires both informal and formal change. Informal change aims “to establish and reinforce shared values and shared ways of doing things that align the organization with its journey to sustainability”, while formal change seeks “to guide behavior through the rules, systems, and procedures”.

Building a circular culture is a gradual process, but as a company’s culture becomes more aligned with meaningful circularity, it is more likely to move in this direction. Companies like IKEA and Selfridges, which have strong sustainability-focused cultures, exemplify this. Their internal efforts put them in a better position to push toward impactful circular initiatives and engage stakeholders effectively.

Lastly, one may ask if and how such a culture could be developed in the case where the person at the top of the pyramid is not interested in such a change. The answer is that while having the CEO’s support can facilitate cultural transformation, it is not solely dependent on leadership at the top. Change can also emerge organically from the bottom up, driven by employees passionate about sustainability. Even small groups of motivated individuals within a company can begin to influence the organization’s culture. I am currently developing a tool based on a student project that explores how activating personal agency can help overcome systemic barriers and contribute to cultural change. This tool will offer practical steps for employees and organizations seeking to initiate such a shift, reinforcing the idea that meaningful transformation can grow from within.

Raz Godelnik is an Associate Professor of Strategic Design and Management at Parsons School of Design — The New School. He is the author of Rethinking Corporate Sustainability in the Era of Climate Crisis. You can follow me on LinkedIn.